The case for sharing clinical trial data

The story behind the first statin and how its development was almost derailed, and the implications of sharing clinical trial data.

This is Saloni! Today’s post is about statins, and the variety of benefits of sharing clinical trial data. I originally published this post on the Abundance and Growth blog by the AGF team, which I’m part of, at Coefficient Giving.

The first statin, mevastatin, was discovered in 1976 by Akira Endo, a biochemist at Sankyo pharmaceuticals in Japan, from a fungal mold growing on rice samples at a grain shop in Kyoto.1

The drug was clearly effective in reducing cholesterol levels, but in 1980, Sankyo abandoned its clinical trials after studies in dogs appeared to show intestinal tumors. The details of these findings were never formally reported; at the time, there were only rumors about what had led the company to shut down its trials.

Meanwhile, Merck was testing a nearly identical compound2, lovastatin, and heard about the decision. They expected it would be a multimillion dollar drug, and so took the sudden halt seriously: what if lovastatin would cause the same side effects?

Merck paused its own trials, and asked Sankyo for further details, but the latter declined to share them.3 So Merck conducted further toxicology studies of their own to understand whether the risks were real, which eventually showed the changes were benign and could be reversed. Three years passed before Merck resumed their clinical trials. When they were completed, they showed a large reduction in blood cholesterol reduction and few side effects. Lovastatin (now known as ‘Mevacor’) became the first statin approved in 1987.4

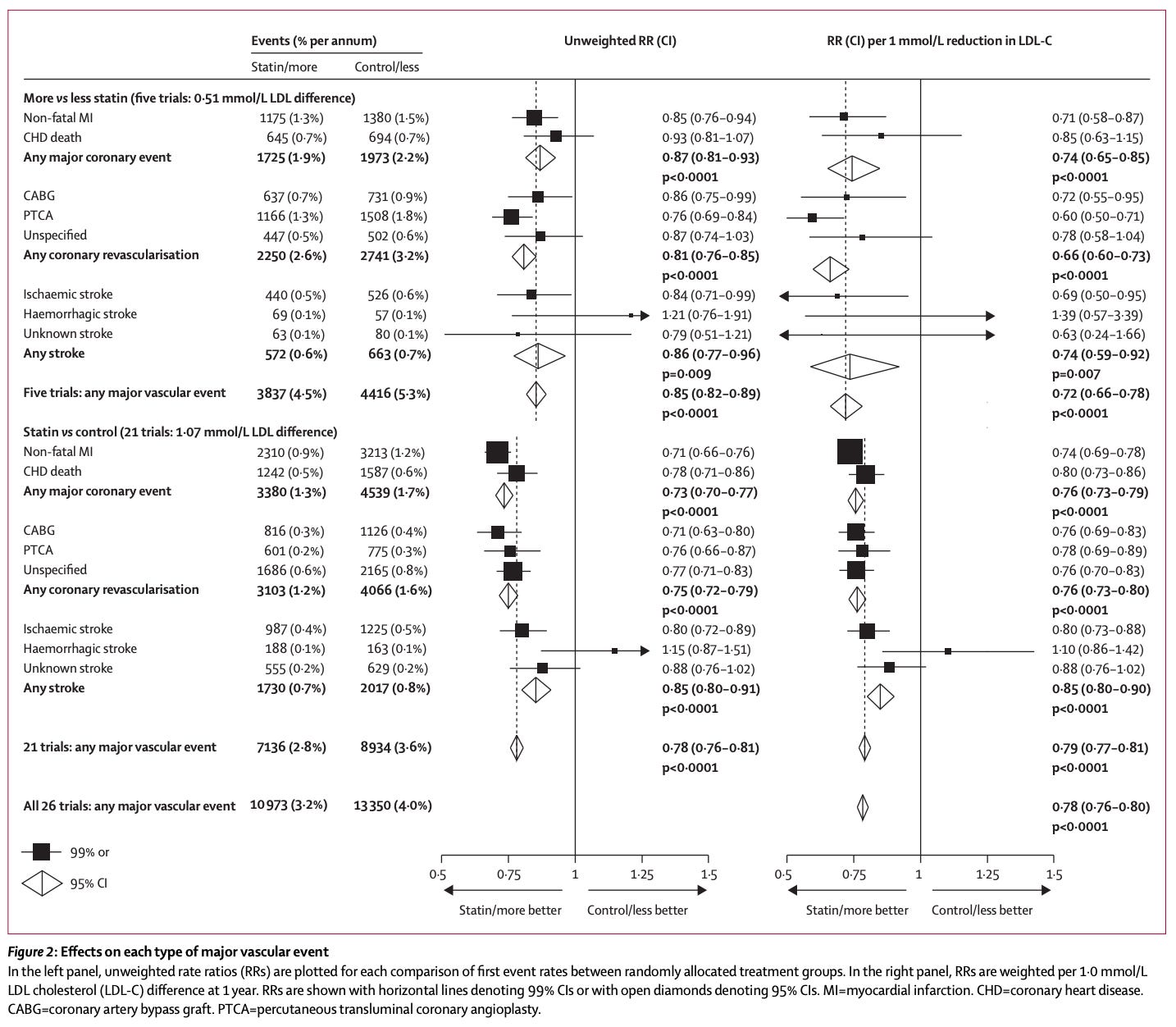

Decades later, after millions of people have been treated and monitored, the evidence shows no increased risk of cancers from statins. They have likely saved millions of lives by reducing the risks of heart attacks and strokes by roughly 20%, and annual mortality rates by 10%.

I’ve been wondering, what if Sankyo had shared its data publicly?

It’s possible that researchers might have analyzed the data further and reached the conclusions sooner. Merck could have avoided redundant studies, and both companies might have reached the finish line, speeding up the arrival of a drug class that would go on to save millions of lives.

Another possibility is that Merck might have instead funded trials for another drug candidate – one that was less similar in structure to Sankyo’s drug, as some within Merck suggested doing. Alternatively, if Merck had never heard about Sankyo’s halted trials at all, they might simply have proceeded, and still correctly found no evidence of harm in their own clinical studies in human patients.

The counterfactual from the story is ambiguous, but it shows that pharmaceutical companies respond to data from other firms. It also highlights a tension: transparency, or even partial transparency, can affect experimentation. When researchers or firms learn early that a similar approach has failed, they may shift toward safer, more predictable projects, at the cost of unexpected successes.

At the same time, access to the underlying data would have allowed other scientists to scrutinize the findings directly, rather than rely on rumors. That would have allowed for better decisions about what precisely to investigate further – helping understand which doses it occurred at and what types of cellular changes were seen, for example – and make more informed decisions about their own research and development plans.

Medicine is an area where transparency has been considered valuable for a long time, and genuine progress has been made in improving it, as I’ll describe in a future post. The consequences extend well beyond the research phase; they can shape decisions about which drugs regulators approve, which treatments insurers cover, and which treatments physicians prescribe.

The stakes are unusually high. In the case of drugs like statins, such decisions touch tens of millions of patients each year5, with hundreds of millions – sometimes billions – of dollars resting on the results of trials.

Transparency at various stages of the process can shape decisions on whether to continue research into drugs, test them in clinical trials, approve them, and how to price them.

If transparency matters this much, what kind of data should be available in practice?

It can seem like an ambitious reform to ask for data at the level of individual patients so the findings can be verified and potentially re-analyzed, because research can involve sensitive personal information, and preparing datasets and documentation for public sharing can be time consuming.

But most highly-cited clinical trials say they will share data, and many say this will be anonymized data from individual patients. Moreover, a few recent efforts have tried to address this problem, including Vivli.org and ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com, with data platforms where clinical trial researchers can deposit their datasets securely.

In practice, however, data from clinical trials remains largely inaccessible and enforcement by journals is weak.

I think there are probably many benefits of transparency in clinical trials, beyond verifying data. They include:

Better meta-analysis. When more trial results are available, researchers can perform meta-analyses that combine evidence across studies. This improves precision and allows for stronger conclusions than single studies can support, for example by helping to identify effects on rare outcomes, such as the effects of flu vaccines in reducing mortality rates, or rare but serious harms.

A recent meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials on statins, for example, found no increase in the risks of most side effects listed on the drugs’ labels (such as brain fog, diarrhea, pain, vision impairment, and 58 other outcomes that had showed no difference in risk between the drug and placebo). Only a few side effects were validated, such as muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis in rare cases, and a slight increase in diabetes. With these conclusions, the researchers suggested that drug labels should be updated.

Understanding inconsistent results. Clinical trials studying similar treatments sometimes reach different conclusions, which leaves uncertainty about whether the differences reflect chance, patient populations, study design, or other factors. By pooling data across studies, researchers can explore these sources of variation more systematically. They could, for example, try to identify when apparent contradictions stem from targeting different biological mechanisms.

Further exploration. Transparency makes it easier to ask new questions of old data. Researchers may want to explore hypotheses that weren’t part of the original study, or revisit results in light of new evidence. When prior trial data are available, many of these questions can be answered without launching entirely new trials. This might include, for instance, when drugs initially developed for one condition show unexpected benefits for another.

Better clinical decision-making. Doctors often have to choose between many drugs for the same condition, without having sufficient data for head-to-head comparisons. Individual trials can rarely answer questions like “Which drug performs best for these patients?” But with more data, techniques like network meta-analyses can help indirectly compare multiple treatments against each other, or derive better conclusions on how to tailor decisions to patients’ characteristics.

Learning how to run trials better. Pooling data across many trials could also help answer questions about studies’ operational characteristics: How does remote monitoring compare with on-site testing? Which trial sites reliably deliver high-quality data? Which eligibility criteria slow down recruitment? Which practices reduce the chances of patients dropping out of studies? These questions could help design trials more efficiently, even though individual research groups rarely run enough trials to study these questions on their own.

Reducing redundancy and wasted effort. Finally, transparency can help avoid repeating failures. Researchers can learn from what succeeded or failed to refine their hypotheses and improve their chances of developing effective drugs in the future. More recent evidence suggests that when reporting the headline results of trials became mandatory, pharmaceutical companies actively monitored competitors’ results and adjusted their own research plans accordingly, avoiding similar studies.

And the value of AI in performing many of these analyses is also constrained by access to the underlying data; the benefits depend on the availability and quality of data available to study.

Taken together, these benefits point to a broader function of transparency in medical research: it allows knowledge to accumulate more efficiently.

By making individual patient data available, studies can move beyond fixed headline results and become part of a cumulative evidence base, giving researchers and clinicians a fuller picture of data that they can use to answer broader questions.

This flow of information can influence the pace of basic research, shape drug development, guide clinical decisions, and ultimately, affect the health of millions of people.

If this sounds similar to the discovery of penicillin, the coincidences go further: both mevastatin and penicillin originated from the Penicillium genus of fungus (Penicillium notatum for penicillin, and Penicillium citrinum for mevastatin). Sankyo began as a company focused on fermentation. Both drugs act by inhibiting a key enzyme in an essential biosynthetic pathway (penicillin blocks the enzymes required for bacterial cell wall construction, while mevastatin inhibits HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis); but while penicillins are irreversible inhibitors, statins’ inhibition is reversible.

Lovastatin and mevastatin differ by only one chemical group: lovastatin has an additional methyl group.

According to the book ‘The Cholesterol Wars’ by Daniel Steinberg (a long-time cholesterol researcher and scientific advisor to Merck), executives at Merck also offered the Japanese pharmaceutical a business deal: “If you help us solve this problem, we’ll share Mevacor [lovastatin] with you in Japan and you can share your second-generation product with us when you’re ready.” The head of Sankyo declined the offer, reportedly saying that he wanted to cooperate but that others objected.

The details are recounted in the books ‘The Cholesterol Wars’ by Daniel Steinberg (based on interviews with Akira Endo [at Sankyo], Alfred W Alberts, and P Roy Vagelos [both at Merck]) and ‘Triumph of the Heart’ by Jie Jack Li.

In 2023, around 50 million Americans were prescribed statins.

If you view clinical trials as primarily being about science, then sharing data is a no brainer.

But to the extent that we should also view clinical trials as part of a political and public relations process, then it’s not clear that transparency is always best. Sunshine laws in politics often reduce compromise by disincentivizing effective but unflattering-looking backroom haggling.

Is there such a thing as too much transparency here? How worried are you about the publication of negative results leading to public backlash against companies or particular medial methodologies?

From what I can tell, neither Vivli nor CSDR offer any compensation for sharing the data. This looks like an incentive problem!