Learning from Australia: towards a "Clinic-in-the-loop" future

The Australian framework for early-stage trials has been around for 30 years and shows speed and safety do not have to come at each other's expense

Yesterday, Senator Bill Cassidy, M.D. (R-LA), chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, released a report detailing legislative and regulatory reforms to modernize the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While many such reports are mere “throat-clearing” exercises, this one proposes several good reforms. I would like to highlight the one that I think would bring the largest boon to the U.S. biotech ecosystem in the short run: a regulatory structure modeled after Australia’s Clinical Trial Notification (CTN) framework.

Australia’s system allows early-stage, investigator-led trials to start significantly faster—often twice as fast as in the U.S.—by bypassing the heavy-duty Investigational New Drug (IND) requirements intended for large-scale commercial trials. Australia has operated this way for 30 years with no difference in adverse safety events, yet the U.S. continues to regulate small, bespoke, tightly monitored studies as if they were massive Phase III trials.

It is, frankly, ridiculous that we have left this “Australian advantage” on the table for three decades while our own domestic pipelines have been throttled by administrative inertia. These small-scale, investigator-initiated trials are not just “preliminary” steps; they are the most information-dense experiments we can perform. In Australia, a researcher with a brilliant idea can move from bench to bedside in weeks.

U.S. companies themselves have increasingly started to move their early-stage trials to Australia where possible. So much so that in informal interviews with founders I have heard of the problem of the Australian trial system becoming “too clogged”.

The regulatory burden associated with launching clinical trials in the United States significantly harms American patients—especially those facing life-threatening illnesses such as cancer. Although the U.S. continues to lead the world in biomedical research and academic science, many terminal cancer patients struggle to access cutting-edge, experimental treatments. Instead, they are often forced to wait for full regulatory approval before these innovative therapies become available.

Implementing such changes would not only help current patients, but also future ones. It is perhaps the highest leverage thing we can do from a policy perspective to speed drug discovery. That is because it is precisely early-stage trials of this kind that enable something I call “Clinic-in-the-loop”: iterative learning in humans, the most important type of learning in biology.

We know this is crucial because some of the most revolutionary therapeutic breakthrough of the last decade (e.g. CAR-T cell therapy) was the hard-won product of two decades of small-scale, iterative “failed” early-stage trials.

To illustrate why these “information-dense” early-stage trials are the true engines of progress, I will draw heavily from an essay I wrote a couple of months ago for Asimov Press titled “Clinic-in-the-loop.”

Clinic-in-the-loop

A couple of months ago, I co-authored an essay with Jack Scannell, arguing that making trials more efficient and informative is essential to breaking Eroom’s Law. Critics of our essay, however, argued that making clinical trials more efficient risks treating biotechnology like a casino.

In their view, making it easier to run clinical trials would risk allowing more potentially harmful drugs to be tested in patients and, instead, biotechnologists should focus on making better drugs that are more likely to gain approval. These critics see Clinical Trial Abundance as accepting the status quo of drug development rather than challenging it.

But this is a misunderstanding.

In fact, Clinical Trial Abundance and better hypotheses for drugs are not merely compatible, but self-reinforcing. Faster testing in the clinic creates a feedback loop: ideas become trials, trials generate rich data (including both successes and failures), these data improve models, and better models inform the next generation of ideas. In this view, the clinic is not an endpoint of discovery but a central component of it.

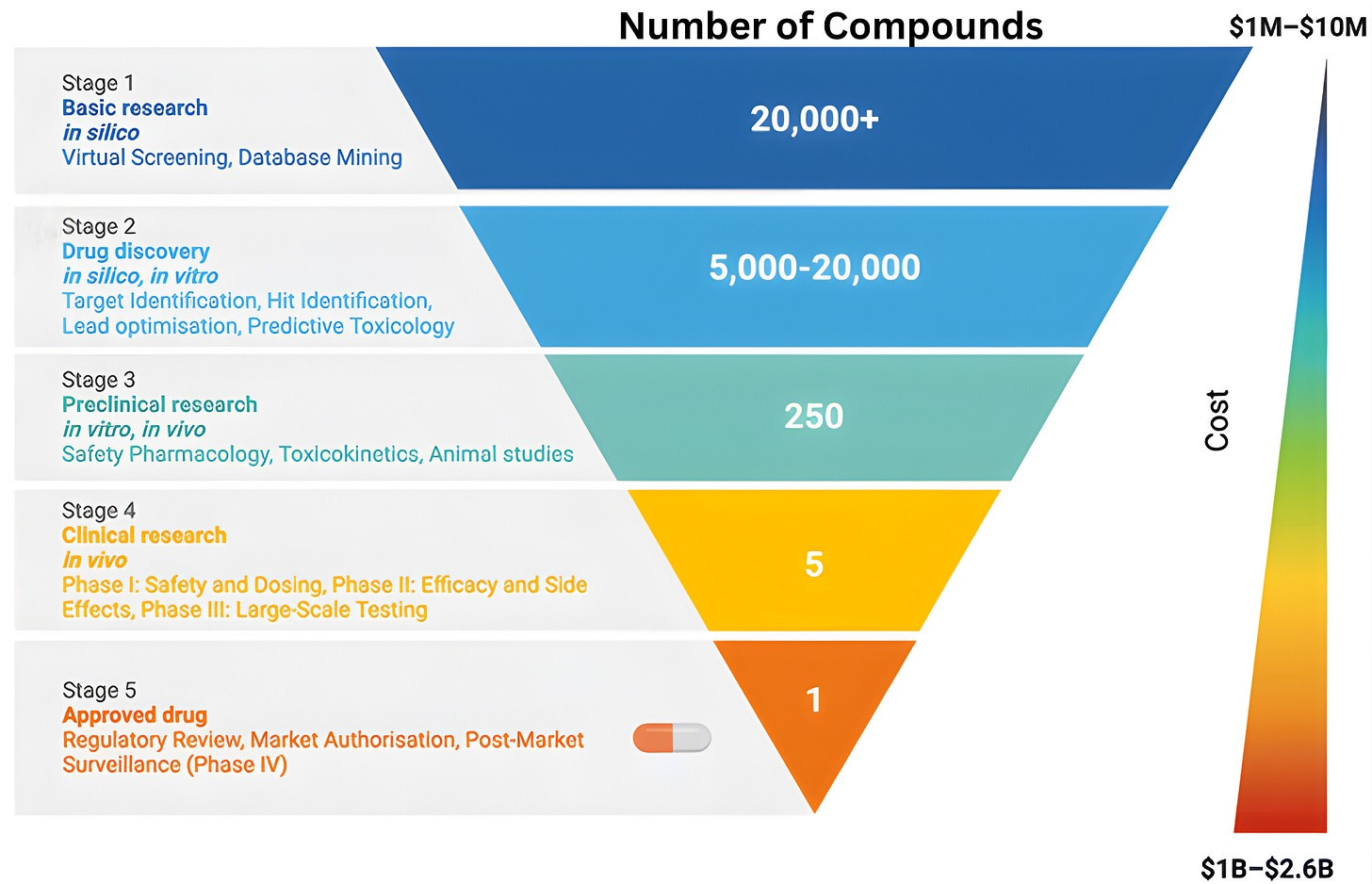

To understand why clinical abundance is important, we must step outside the prevailing view of clinical testing as a mere “validation step” for scientific ideas. The familiar funnel metaphor of drug discovery, depicting a linear progression from basic science to regulatory approval, reinforces the flawed notion of clinical testing as a passive filter designed to screen pre-existing ideas. While this model is narrowly correct in a regulatory sense, it obscures the clinic’s role as an active engine of discovery.

The reality is that clinical trials rarely just deliver a “yes/no” verdict on a drug’s efficacy. Instead, the history of drug development shows that many successful therapies emerged only after initial versions failed in specific, informative ways. When a trial fails, it provides a unique physiological stress test that reveals exactly where a drug’s design fell short. By collecting data from “failed” trials, we can transform negative results into experimental corrections for the next iteration.

Consider CAR-T cell therapies. Once thought implausible or risky, CAR-T therapies now deliver long-term, treatment-free remissions in cancers where relapse had been almost certain.1 In pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and aggressive B-cell lymphomas, for example, CAR-T has cured patients who, previously, had been given only months to live.

CAR-T therapy works by turning a patient’s own immune cells into living drugs. Doctors collect T cells from the blood, genetically reprogram them to recognize a protein on cancer cells, and reinfuse the modified T-cells into the patient. These engineered cells expand inside the body, move to tumor sites, and destroy malignant cells.

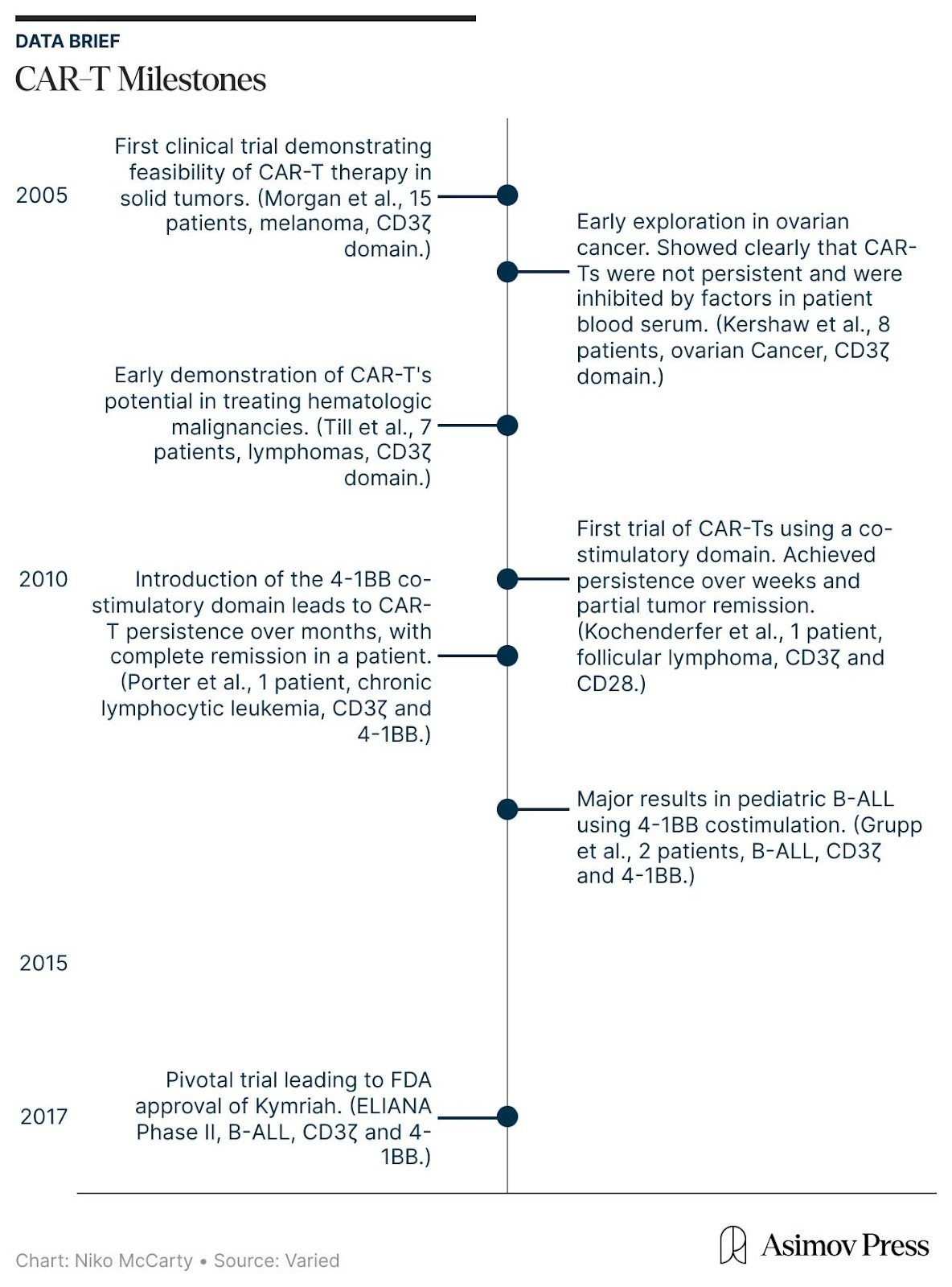

In 2017, the FDA approved Kymriah, the first CAR-T therapy, for children and young adults with relapsed or refractory B-ALL, a cancer of arrested development in which immature blood cells, specifically B cells, multiply out of control while failing to mature into viable immune cells. Relapsed B-ALL is the most severe form of the disease, because it means the cancer has returned after prior therapy. Even with aggressive care, only 10-20 percent of patients with relapsed or refractory B-ALL survived beyond five years.

Against this backdrop, Kymriah received accelerated approval from the FDA based on results from the Phase II ELIANA trial, a global, multicenter study sponsored by Novartis. In ELIANA, 82 percent of treated patients achieved complete remission, and subsequent follow-up analyses revealed that five-year survival rose to approximately 55-60 percent.

ELIANA was not a sudden breakthrough, though. It was, rather, the culmination of nearly two decades of clinical studies. During this period, CAR-T therapies evolved through repeated failure in the clinic, as careful studies of underwhelming results spurred new ideas to correct them. The ELIANA trial was led by investigators at the University of Pennsylvania, a group that had spent years studying CAR-T cells directly in patients well before regulatory approval.

In the mid-2000s, the earliest CAR-T therapies first entered human testing. And they emerged from a fundamental question: is it possible to engineer and redirect the T cell’s innate killing power against malignant cells?

Two well-established biological concepts made this seem plausible. First, T cells are extraordinarily cytotoxic.2 However, their natural activation is governed by a “layered permission” system, meaning they cannot recognize targets directly, but must wait for other cells to process and present protein fragments in a precise molecular context. While this evolutionary safeguard keeps us from being attacked by our own immune system, it also provides cancer with many opportunities to evade detection by suppressing these signaling pathways.

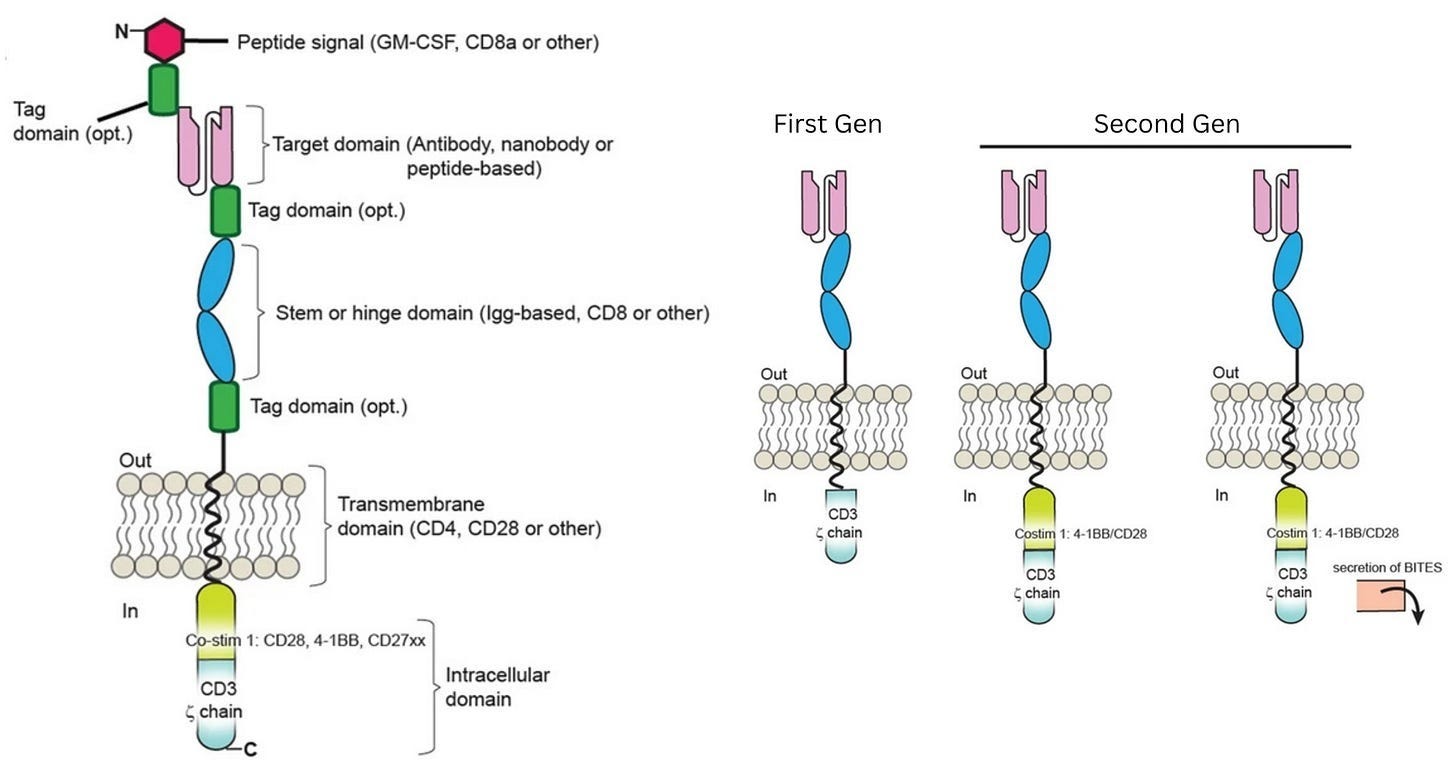

To bypass these safeguards, researchers relied on a second insight: the ability of antibodies to bind directly and precisely to proteins on the surface of cells, called antigens. By equipping T cells with a synthetic Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR), bioengineers created a functional shortcut that bypassed the need for permission systems. This receptor uses antibody-style recognition to lock onto a cancer cell and is wired directly to CD3ζ, a signaling molecule that triggers the T cell’s internal “kill switch.” The moment the receptor engages its target, it flips the internal switch, activating the cell’s killing program.

In laboratory experiments, these first-generation CAR-Ts were formidable, displaying antigen recognition and potent killing power against tumor cell lines. Yet, this in vitro prowess vanished in patients and did not yield durable clinical responses. Understanding why this happened, though, was not simple. The failure could have been caused by a breakdown in in vivo antigen recognition, poor signaling strength, or other defects that only emerged after the cells were injected into the body.

Progress in understanding why came from treating first-in-human trials not simply as therapeutic attempts, but as opportunities to learn. These information-dense studies were conducted throughout the mid- and late-2000s and were relatively small (usually enrolling fewer than ten patients). However, they were designed to be maximally revealing. Researchers used many tools to monitor CAR-T persistence and activity in the body, turning information from a small number of patients into a mechanistic understanding.

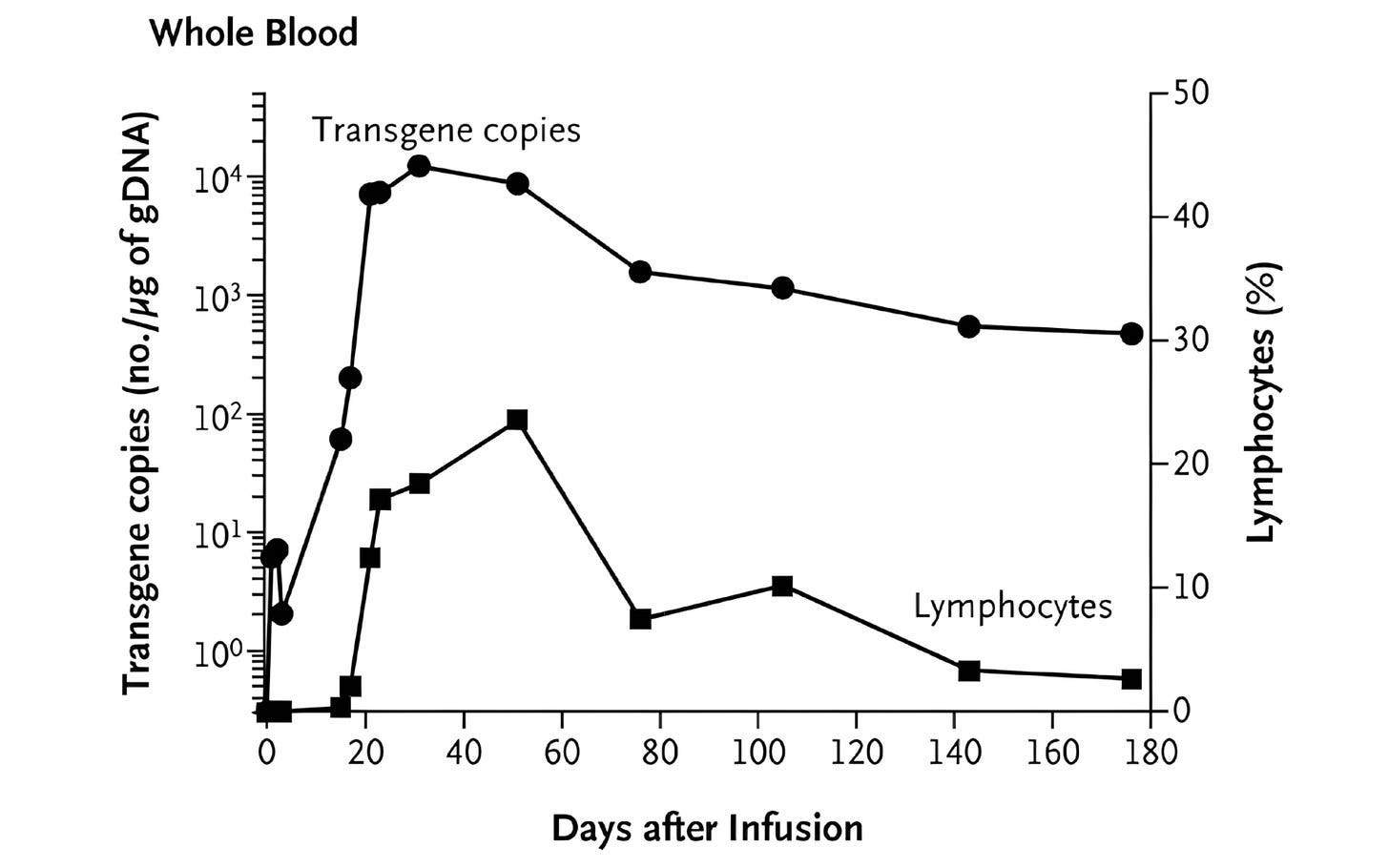

One such tool was quantitative PCR (qPCR), a lab method that detects and counts specific DNA sequences, which allowed researchers to measure how many CAR-T cells were in patients’ blood. This showed that CAR-T cells successfully entered the body and were easy to detect after infusion. But the signal quickly faded, suggesting that the cells died off quickly. Other experiments shed light on the problem: CAR-T cells could recognize and eliminate cancer cells in patients — meaning antigen recognition was working — but their functional activity fell over time, suggesting that something in the blood was blocking them.

At this point, the diagnosis of why first-generation CAR-T therapies were failing matched long-standing insights from basic immunology. Decades of research had shown that T cells are not governed by a single on-off switch: signaling through CD3ζ provides only the first activation signal. To keep working, T cells need additional “co-stimulatory” signals,3 delivered through receptors such as CD28 or 4-1BB. First-generation CARs had been designed to deliver signal one without signal two, which explained their poor performance.

This hypothesis guided the next wave of clinical experiments, which investigated whether adding a costimulatory domain would make CAR-T cells more effective at clearing tumors in vivo.

The field-defining result came from Carl June’s group at the University of Pennsylvania. June and colleagues explored a costimulatory domain called 4-1BB. In a first-in-human study published in 2011, they treated a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia using CAR-T cells containing both CD3ζ and 4-1BB. They also administered a dose that was remarkably small by cell therapy standards at that time: just 1.5 × 10⁵ CAR-T cells per kilogram of body weight. (A first-generation CAR-T trial targeting renal cell carcinoma, published in 2013, used a dose more than 100-times higher.)

What followed was unprecedented. The CAR-T cells multiplied more than a thousandfold in patients, at their peak comprising a large fraction of immune cells in the blood. The CAR-T cells also persisted for months. Now, at last, CAR-T cells were a long-lived and self-maintaining immune population. Many cancer patients treated with these second-generation CAR-T therapies have achieved complete remission.

The next step, though, was asking whether the same CAR-T behavior would work in a faster, more aggressive blood cancer, such as B-ALL. In 2013, Carl June’s lab reported striking results in two children with relapsed B-ALL, again showing that the engineered T cells could multiply, persist, and drive cancer into remission.

All of these lessons were built into ELIANA, the study that ultimately supported Kymriah’s approval. Led by Stephan Grupp, who had treated the earliest pediatric patients and worked closely with June, ELIANA translated the early insights into standardized practice. This trial codified chemotherapy given before CAR-T infusion, scaled up cell manufacturing, and measured success using tools like qPCR.

Viewed through this lens, clinical trials are not an alternative to basic science, but rather a mechanism within it that closes a feedback loop. Foundational immunology, antibody engineering, and molecular biology made first-generation CAR-T cells possible in the first place, but early human trials quickly revealed that these designs were incomplete and suggested ways to fix them.

Yet theory alone did not prove this would work; the expansion and persistence observed with 4-1BB–based CAR-T cells came as a genuine surprise even to the therapy’s designers. “It was unexpected,” they reported, “that the very low dose of chimeric antigen receptor T cells that we infused would result in a clinically evident antitumor response.”

This shows why the “casino biotech” critique is flawed. It assumes that experimentation simply reveals a fixed probability of success. But trials can change those probabilities. When clinical testing is understood as part of a continuous feedback system, optimizing trial efficiency is not about accepting failure but about learning fast enough to make success more likely.

The most discovery-rich experiments are often not massive Phase III trials, either, but small, academic, investigator-initiated studies that sit close to the design loop.4 These are also the trials most burdened by regulatory, institutional, and manufacturing bottlenecks. And also the trials that adopting an Australia-like model would impact.

How the Australian model works in practice

The Australian Clinical Trial Notification (CTN) framework differs fundamentally from the current U.S. system in how authority is allocated between ethics committees and the national regulator, and when regulatory scrutiny occurs. In Australia, the Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) conduct the primary scientific, ethical, and safety review of a proposed early-stage clinical trial. Once an HREC approves a study, the sponsor submits a streamlined online notification to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), and the trial may begin shortly thereafter.

There is no requirement to submit a full Investigational New Drug–style dossier to the regulator before initiation for these early-stage, bespoke trials. By contrast, in the United States, sponsors must submit a comprehensive IND application to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under 21 CFR 312 before beginning a clinical trial. The FDA performs its own scientific, toxicology, and chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) review, and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) separately review ethical considerations under 45 CFR 46. This results in parallel review streams and often significantly longer timelines before a trial may commence.

In practice, the Australian model delivers what can be described as stage-appropriate review. Regulatory scrutiny is not diminished. Rather, it is calibrated to the specific risks and uncertainties that characterize that phase of development. Early-stage trials have high failure rates, and many investigational products never move beyond first-in-human studies. Requiring extensive upfront documentation and full manufacturing packages for programs that are likely to stop early adds significant cost and delay without meaningfully improving participant safety at that stage.

Early development is a learning process. Sometimes even the underlying hypothesis is reconsidered as real human data become available. A regulatory framework that allows this kind of rapid, well-monitored iteration better reflects how drug development actually works. By focusing oversight on the risks that are most relevant in early trials—rather than imposing requirements designed for later-phase studies—the Australian system promotes efficient evidence generation while still maintaining strong safety protections for participants.

Australian site activation averages approximately two months from final protocol, and TGA acknowledgment of CTN submissions occurs within days. In the United States, IND review and resolution of regulatory questions frequently extend for several months before enrollment can begin. Such a difference in timelines can be particularly important for an early-stage biotech company struggling to survive on limited cash.

Why has this not been done before?

Knowing that Australia has operated this framework safely for 30 years—and that these trials are the highest-leverage instruments in biology—the question becomes: why has this been left on the table? Why is the U.S. biotech engine idling at a red light that doesn’t need to be there?

The answer lies in a fundamental distortion of Washington’s health policy priorities. In D.C., “health policy” is almost exclusively synonymous with demand-side economics: Medicare, drug pricing, and reimbursement. The supply-side—the actual machinery of how we discover and test new biology—is remarkably ignored.

This policy stagnation is a classic “tragedy of the commons” problem. There is no natural, deep-pocketed constituency for early-stage trial reform:

Big Pharma uses its political capital primarily to protect reimbursement and pricing. For a multi-billion-dollar incumbent, saving a few million dollars or six months on an early-stage trial is a rounding error. Furthermore, their model is often to let others take the early risks and then acquire the survivors once they’ve reached later-stage validation, meaning that they often are not the ones carrying out these trials. By the time a biotech has produced a drug that looks promising, a few millions extra due to early trial costs is nothing.

Small Biotech would be a more direct beneficiary of these reforms, but these startups rarely have the time, money, or lobbying presence to advocate for systemic change in D.C. They are too busy trying to survive the very bottlenecks we are discussing.

The Commons. Of course, the primary beneficiaries of these reforms are ultimately The Commons. If more drugs are tested in early-stage trials, all of us get more and better drugs. However, those doing advocacy on behalf of the commons have often had an approach that focuses much more on the distribution of what exists (“demand-side”) than creating abundance (so working at the “supply-side” level).

This is why the emergence of the “Progress” community is so vital. Organizations like The Roots of Progress and IFP are filling the gap left by this tragedy of the commons. They are doing the “un-incentivized” work of advocating for the structural plumbing of science—the boring, high-leverage regulatory reforms that Big Pharma ignores but that the future of medicine depends on.

We need progress-minded individuals to step into these gaps, supported by institutions that understand that supply-side policy reforms centred around Clinical Trial Abundance are key to the future of medicine. Senator Cassidy’s report is a rare sign that this message is finally reaching the most important echelons and it is an opportunity we cannot afford to waste.

It looks like the UK’s MHRA is moving in a similar direction to Australia’s CTN framework with its new package of clinical trial regulations coming into force in April:

"Under the new rules, around one in five studies are expected to move onto a fast-track notification route, which will allow lower-risk trials to start sooner, while maintaining high safety standards and freeing up experts to focus on complex and early-phase studies. The MHRA will also introduce a 14-day assessment route for phase 1 trials, adopting an innovative stepwise approach, restoring a rapid pathway for the earliest testing of new medicines in people – a key draw for global developers deciding where to base their research." Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/patients-to-benefit-sooner-as-uk-boosts-clinical-trials-attractiveness-with-faster-assessments-and-agile-regulation

It's not a full CTN equivalent (there's still a formal authorisation step), but the overall shift toward risk-proportionate, faster approvals feels very much in the same spirit.